Post by amun on Nov 23, 2011 7:38:40 GMT -5

Here's an interesting physical anthropology piece I thought was worth sharing.

The Mediterranean race in East Africa

In the present section we shall consider what is today a second southern periphery of the white racial stock; peripheral in this case to the world of the African Negro. East Africa, with its highland plateaux of Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Kenya, and with its treeless grasslands, forms an environmental zone suitable for the economies of highland agriculture and of pastoral nomadism. Its early connections lie with the north and east, with Egypt and Arabia, rather than with the equatorial forests to the west.

The highlands of Ethiopia, according to studies conducted by economic botanists, seem to contain a number of indigenous varieties of cultivated cereals and legumes.55 It is possible, but by no means established, that these highlands formed one of the primary centers of Old World agriculture, in which the Neolithic economy originated. It is also possible that part of the agricultural impulse which initiated the high civilization of ancient Egypt was derived from this source.

Later than the development of highland agriculture in East Africa was the introduction and diffusion of pastoral nomadism. The cattle complex, with its elaborate set of social restrictions and of social differentiation on the basis of wealth in herds, was introduced from India by way of southern Arabia, along with the humped zebu, at some none too distant period, probably as late as the first millennium B.C. Its diffusion passed southeastward into the Lake Region, where it was taken up by Bantu peoples and spread, in modern times, as far south as the Cape of Good Hope, where an earlier version of the same complex had already arrived, in the hands of the Hottentots.

In the Horn of Africa region, however, and northward into Egypt, the humped cow is replaced by the more thirst-resisting camel; camel nomads are found in all regions in which agriculture is impractical. The antiquity of camel nomadism in East Africa is unknown, but it cannot be as old as in Arabia, for the camel is an Asiatic animal.56 Camels did not appear in any numbers in North Africa east of the Nile before 300 A.D., but they must have been earlier than that in East Africa, having been introduced, at some unknown period, from Arabia by way of Suez, of the Bab el Mandeb, or simply across the Red Sea.

The living peoples with whom this section is concerned live by all three economies mentioned—highland agriculture, cattle nomadism, and camel nomadism. They are the whites and near-whites who live east of the equatorial forests, of the Nilotic swamps, and of the deep escarpment of he Blue Nile. They are the Gallas, the Somalis, the Ethiopians, and the inhabitants of Eritrea. They speak languages of two stocks—Hamitic and Semitic. Of the two, Hamitic is the older, for Semitic speech was introduced by colonists from the Hadhramaut only a few centuries B.C. The Hamitic linguistic stock is divided into three families of languages: (1) Libico-Berber, (2) Ancient Egyptian and its derivative Coptic, (3) Cushitic. These families seem to be nearly as closely related to Semitic as they are to each other,57 so that a Semito-Hamitic superstock has been postulated, with Semitic as the fourth branch. Ancient Egyptian, according to a recent analysis,58 may have been merely a blend of the other three. The East African Hamites, however, all speak languages of the Cushitic family, and the word Hamitic, when applied to East Africans, is equivalent to Cushitic.

Our knowledge of the racial history of East Africa in antiquity is limited to the southern frontier of the present Hamitic linguistic area. Excavations in Kenya and Tanganyika have uncovered remains of a tall, extremely long-headed, Mediterranean racial type, with a tendency to great elongation and narrowness of the face, in pre-Neolithic times. In Mesolithic times, if not earlier, some of these Mediterranean skeletons show evidence of negroid admixture.59 The country east of Lake Victoria may be taken as the southern boundary of the area occupied by this race, since to the south all known sapiens skeletal remains belong to the ancestors of Bushmen. The center of this area, and its northern boundary, are unknown, owing to the lack of archaeological work in Ethiopia and the eastern Sudan. The present distribution of a similar and without doubt derivative racial type coincides with that of Hamitic languages, and for that reason the term “Hamitic Race,” has been frequently employed.

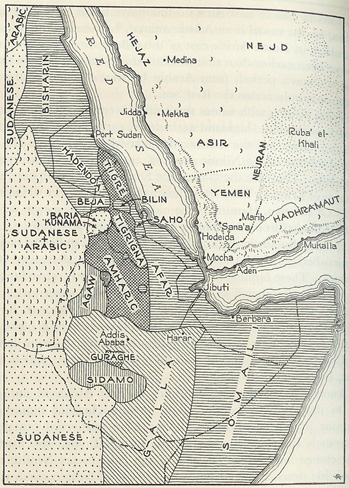

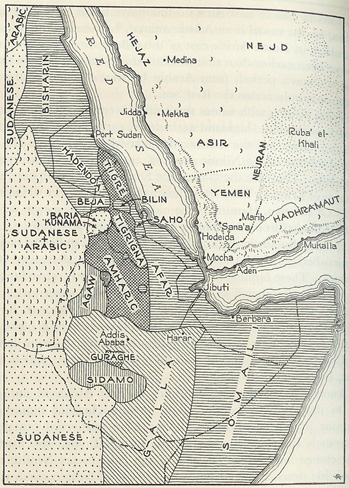

Linguistic map of the East African Hamitic Area

The Cushitic languages of East Africa and of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan are shown in parallel line representation. The Semitic languages of this region which are derived from Geez are designated by cross-hatching. It should be noted that Tigrigna is the language of Tigré Kingdom; the Tigré language, however, is a related coastal speech. Sudanese Negro languages are shown by means of large dots, Arabic by means of vertical crescents. (Adapted from Meillet and Cohen, Les Langues du Monde.)

The living inhabitants of the Abyssinia-Somaliland-Eritrea area may be divided into the following groups:

(1) The Highland Cushites: Descendants of the pre-Semitic agricultural population of the northern Ethiopian plateau, speaking early Cushitic dialects. The most numerous and best known of this scattered group are the Agaus, peasants and agricultural serfs living mostly in the kingdom of Gojjam, in the Lake Tsana country.

(2) The Sidamos: The corresponding pre-Semitic agricultural population of the present Galla country, living in the midst of Galla tribal territories, and in small separate kingdoms of their own, in southwestern Ethiopia. The best known Sidamo state is that of Kaffa, whose name has been given to coffee. Throughout the Galla country, the numerous peasant class consists largely of linguistically altered Sidamos.

(3) The Amharas: This is a general name applied to the Ethiopians proper, members of the four kingdoms of Tigré, Amhara, Gojjam, and Shoa. The Guraghes, who live south of Addis Ababa, speak Amharic, as do all the others named except the Tigrés, whose language is a parallel derivative of Geez. These people are the descendants of the Hadhrami invaders of the late pre-Christian era, and were, until the Italian conquest of 1935—37, the dominant people of Ethiopia.

(4) The Gallas: The inhabitants of most of southwestern Ethiopia, including the country as far north and east as Addis Ababa, are Gallas; descendants of a warlike confederation of nomadic tribes who invaded Ethiopia from the southwest in the sixteenth century. The original Gallas, who came in great numbers, were cattle people with the traditional East African dislike for agriculture or menial occupations, and settled down in their present territory as aristocrats. Galla society today is divided into four classes: the Oromo, or Galla proper, the aristocrats; the Tumtu or blacksmiths, the subservient class of artisans who are also farmers; the Faki, a low caste of tanners; and the Watta, outcaste hunters who live in separate villages. The Oromo have, for the most part, submitted to the pursuit of agriculture, while continuing at the same time their cattle raising.

(5) The Somalis: The whole Horn of Africa, including the three Somali lands and the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, is occupied by various tribes of Somalis, nomadic Hamites who profess Islam and claim descent from Arabian missionaries. Their origin is not clearly known, but it is evident that there must have been some Galla as well as Arabian mixture, grafted onto a local Hamitic population.

(6) The Danakil (also called Afar): In southwestern Eritrea and adjacent parts of the desert of northeastern Ethiopia, as well as in part of French Somaliland, live the Danakil, tribesmen culturally related to the Somalis, who also claim Arabian ancestry. North of the Danakil in Eritrea live other tribes of the same general type. The Somalis, Danakil, and their northern relatives form part of a continuous belt of nomadic Hamites reaching from the Horn of Africa to Egypt; the northern representatives, however, from the Eritrean Beja to the Egyptian Bisharin, have been subjected to strong admixture with Sudanese negroes.

(7) Negroes in Hamitic Territory: In Eritrea the tribes of Baria and Cunama, in the midst of Hamitic-Tigré territory, probably represent, in the linguistic sense at least, and eastward thrust of Sudanese negroes. In Ethiopia proper many Shankalla, negroes brought as slaves from the Blue Nile country, have propagated both as a slave population and through mixture. In Italian Somaliland, it is said that some of the slave tribes subservient to the Somalis speak Bantu. The speech of the Wattas may also be neither Hamitic nor Semitic.

The study of the physical anthropology of this ethnologically and historically complex region may be said to have barely begun; nevertheless it has progressed far enough to warrant reasonably accurate statements as to the racial characters of the more numerous and better known peoples.60 Before proceeding further, it may be well to state that all of the peoples of this “Hamitic” area, whether Hamitic or Semitic in speech, represent a blend in varying proportions between Mediterraneans of several varieties, especially of the tall, Atlanto-Mediterranean group, and negroes. Other elements include, of course, the Veddoid brought in solution from southern Arabia; there is also a possibility of traces of dilute pygmy and Bushman blood in southwestern Ethiopia and Somaliland, although neither of these has been proved. Needless to say, the Gallas and Amharas have mixed with each other greatly in the regions in which they have been in contact; both the Amharas and Gallas have absorbed the earlier Cushitic agricultural peoples in great numbers. The most important single influence has been the infiltration of negroes, through the slave trade, into the entire Ethiopian plateau region. So extensive has this infiltration been that it is unlikely that a single genetic line in the entire Horn of Africa is completely free from negroid admixture; but individuals may be found among the Amharas, Gallas, and Somalis who show no visible signs of negro blood. These individuals are extremely rare. On the whole the negroid element in the Hamitic cannot be much more than one-fourth of the whole, but it has penetrated every ethnic group and every social level. Just when this penetration had become complete we do not know, but one suspects that it had already occurred by the sixth century A.D., when the Ethiopians ruled the Yemen. The Gallas, despite their tradition of descent from white men, were already partly negroid at the time of their arrival in Ethiopia.

Despite this negroid penetration, and despite a mixture between non-negroid elements, the four ethnic Units of Amharas, Gallas, Sidamos, and Somalis are all statistically distinct from each other.61 What evidence we have for the Agaus suggests that this people constitutes a fifth anthropometric entity. As one would expect, the more purely Hamitic peoples, such as the Agaus, Gallas, and Somalis, are taller than the Amharas. All of these three have stature means ranging from 169 to 174 cm., while 172 cm. seems to be the central mean for all of them. The Semitic speakers range from a mean of 164—167 cm.62 for the Tigré, the most nearly Arabian of the four main groups, to 167—169 cm. for each of the other three, while a series of varied Ethiopians, mostly from Shoa, and measured in Addis Ababa, rose to the mean of 169 cm. This latter figure may reflect Galla mixture—for Addis Ababa is in Galla territory—or selection. The Sidamos, in contrast to the Agaus, are apparently short (164 cm.).

In bodily build and proportions, all groups are much the same. The predominant type is leptosome, with a relative sitting height index of 50 to 51, a relative span of 103, and a relative shoulder breadth of 21. Long legs and relatively short arms, narrow shoulders, and even narrower hips, are the rule. Few Ethiopians of any category are thick-set, and what little corpulence is seen hangs ill on fine-boned frames. The hands and feet of all but the palpably negroid are small and extremely narrow, the lower legs and wrists usually spindly and ill-muscled. This attenuation of the distal segments of the limbs reaches its maximum among the Somalis. The Sidamos, who are by far the most negroid of the Ethiopian peoples, have the broadest shoulders in proportion to their height, and the narrowest hips.

There can be no doubt that the tall stature of the Gallas, Somalis, and Agaus is an old Hamitic trait, since both the negroid Sidamos and the Semites of Hadhramauti origin are much shorter. The tallness of this East African Mediterranean strain stands in contrast to the moderate stature of the Mediterranean Arabs across the Red Sea, and constitutes a characteristic difference between them. The bodily build of the African Hamites is typically Mediterranean in the ratio of arms, legs, and trunk, but the special attenuation of the extremities among the Somalis is a strong local feature,63 which finds its closest parallels outside the white racial group, in southern India and in Australia.

The different groups studied in Ethiopia share a tendency to dolichocephaly or mesocephaly, and to a narrow face form. In the measurements of the head and face, all are fundamentally Mediterranean, and the negroid traits manifested in the soft parts do not reveal themselves in the measurements, except in nose breadth and in the biorbital and interorbital diameters. The heads are larger than those of the Yemeni Mediterraneans; Amharas (in the sense of Semitic-speaking Abyssinians) have vault dimensions of 194 mm. (length) by 150 mm. (breadth) by 127 mm. (height); these figures could apply as well to Nordics as to Abyssinians. The mean cephalic index of 77 or lower64 for Amharic speakers is in the dolichocephalic to low mesocephalic class; the smaller diameters and higher index of the present-day Hadhramaut population seem to have yielded to the greater size and dolichocephaly of the indigenous Hamitic farmers, as far as the total group is concerned. There is, however, some evidence that while the Tigré people are strongly dolichocephalic, brachycephaly may be common in the kingdoms of Gojjam and Amhara.65

The Gallas are on the whole smaller headed than the Amharas, but also mesocephalic. Mesocephaly is also the prevalent head form of both Agaus and Sidamos; among the latter the mean cephalic index is 78, and there is a definite brachycephalic minority. So far the inhabitants of the Abyssinian plateau, whatever their speech and ethnic origin, are dolichocephalic or mesocephalic, and comparable to Mediterraneans elsewhere, especially, as we shall later see, to North African Berbers, as well as to North European Nordics. Among the Sidamos, however, the vault is lower (124 mm.) than among Amharas and Gallas. The Somalis, as contrasted with the highland bloc, are smaller headed and purely dolichocephalic, with vault dimensions of 192 mm. (length) by 143 mm. (breadth) by 123 mm. (height), and a mean cephalic index of 74.5. In this they resemble closely the finer Mediterranean type in Yemen, and some of the northern Bedawin.

Facially this division between highianders and Somalis is accentuated. The highlanders have minimum frontal means of 104 mm. to 106 mm.; the Somalis of 102 mm. The bizygomatics of the first group fall at 134—136 mm., of the Somalis at 131 mm. The bigonials of the highianders have means of 101—102 mm., of the Somalis, 96 mm. All are narrow faced, but the Somalis approximate a world extreme. The forehead is in all groups notably wider than the jaw, which reaches a record in narrowness among the Somalis. In face breadths as in vault dimensions the less extreme highland Ethiopians might as well be Nordics as negroids.

The total face heights of the four groups under consideration range from 122 mm. to 124 mm.; the upper face heights from 71 mm. to 74mm. It is interesting to note that the Sidamos, who are the most negroid, have the broadest foreheads, bizygomatics, and bigonials, the longest menton-nasion heights, and by far the longest upper face heights, of the entire group. It is the Somalis whose upper face height is shortest. All four are leptoprosopic and leptene, the Somalis hyperleptoprosopic.

The noses of Somalis, Amharas, and Gallas are leptorrhine, with nasal indices of 66, 68, and 69, respectively. This regression indicates with some accuracy the relative amounts of negro blood. The Sidamos, with an index of 71, are mesorrhine and the most negroid. In accordance with the principle that the most negroid have the longest as well as the broadest faces, the Sidamos have the longest and broadest noses, with a mean height of 55 mm., and breadth of 39 mm. The Somalis, whose noses are narrowest, also have the smallest, 52 mm. by 34 mm.

In the measurements of the external eye the Somalis differ again from the highlanders; their mean interorbital diameter of 31 mm. is narrow, while that of the highianders, 34—35 mm., approximates a negroid condition. In the biorbital, the distance between the outer eye corners, the Somalis are narrowest, with 91 mm.; the Sidamos the broadest with 96 mm.

Our Survey of the metrical characters of the inhabitants of the Hamitic racial area has brought several facts to light; the agricultural population of the Ethiopian highlands, both indigenous and imported from Arabia, belongs to a tall, dolichocephalic to mesocephalic, leptoprosopic, moderately leptorrhine race, which is Mediterranean in metrical position and cannot be distinguished, on the basis of the more commonly taken measurements, from blond and brunet Mediterraneans of Europe and North Africa. The Somalis, on the other hand, belong to an extreme racial form; extremely linear in bodily build, extremely narrow-headed and narrow-faced, with a special narrowness of the jaw. The relationship of the Somalis, on metrical grounds, is with some of the peoples of India as much as with the Mediterraneans elsewhere. The leptosome tendency, and the narrowness of the face, remind one of the same tendency found among the mixed Bedawin group of the Hadhramaut. It cannot be attributed to negro-white mixture, for that phenomenon, as witnessed among the Sidamos, has produced a heaping of characters, resulting in an enlargement of both sagittal and lateral diameters of the face, in some cases in excess of either the Hamitic white or the negroid parent. Upper face height and nose height are especially affected. The Somali face and nose are not long, they are merely narrow. The extremely long faces and noses found among the Ba-Hima, the noble class of the Baganda, and supposedly of Galla origin, have acquired a social value, and far exceed those of the Somali. In this tendency to attenuation of the face, we are reminded of Oldoway man and some of the Elmenteita skeletons. This tendency is an extremely old one in East Africa.

In the skin color of the Arabs, however dark the exposed and tanned parts might be, the unexposed epidermis was always considerably lighter. A fundamental difference between Arabs and Ethiopians is seen in this feature, for the latter are usually the same in skin color all over. In fact, the foreheads of Ethiopians are in some instances lighter than their shirt-protected bodies. In the three highland groups of Amharas, Gallas, and Sidamos, the Amharas are lightest skinned, with the majority of shades concentrated in the medium brown category, between von Luschan #21 and #25; individually the series runs as light as #13, a brunet-white, which is approximately the color of the former Emperor, Hailie Selassie. At the other extreme it reaches #34, which is almost jet black, nearer the color of the great Emperor Menelik II. Thus among the Amharas almost the entire range of human skin color intensity is covered, with the exception of rosy or pinkish-white, which probably does not exist among Ethiopians. The Gallas run somewhat darker, with their concentration in the medium to chocolate-brown class, between #22 and #29; their range is somewhat less than that of the Amharas, and the rare brunet-white of the former is in some cases replaced by a yellow of Bushman intensity. Most of the Sidamos are darker than #30, and are thus really dark brown or black.

So far, the progression in skin color has followed that of relative amounts of negro blood, with an immense range covered; the inheritance of skin color in the Ethiopian highlands is not strictly Mendelian in a simple sense, nor is it by any means a case of ordinary blending. If there was ever a rosy-white shade in the non-negroid element, it has long since disappeared. Among the Somalis, however, an entirely different situation is found, for the majority are lumped around the von Luschan #29. Numbers 27 and 30 account for most of the others; hence there is a single and characteristic Somali color, which is a rich, glossy, chocolate-brown, which accounts for seven-eights of the entire Somali group. A very few are darker, and individuals are as light as light brown, in a very few cases as light as Arabs. The contrast between highland Ethiopians and Somalis in skin color is so great that one must postulate that the original non-negroid narrow-bodied and narrow-faced strain which the living Somalis represent was not white skinned in any sense of the word, for the Somalis are the least negroid people in East Africa.

The Ethiopians themselves are extremely conscious of differences in skin color, and divide themselves into four groups: “Yellow,” “Yellow-Red,” “Red,” and “Black.” These groups do not correspond very well with the von Luschan scale, but represent the product of centuries of local experience, and are perhaps more significant from the genetic standpoint. A jury of Amharas and Gallas called 20 per cent of the former “Yellow,” as against 8 per cent of the latter; only 2 per cent of either was “Black.” In both, the “Red” class was the most numerous; with 47 per cent of Amharas, and 70 per cent of Gallas. Most of the few Sidamos studied are evenly divided between “Red” and “Black.” This system could not be applied to the Somalis, whose characteristic hue defied classification.

In hair form the Ethiopians also have their own system, which hardly agrees with ours. It has three divisions; lüchai, meaning “straight,” gofari, meaning “curly,” and another term which signifies extremely negroid, or peppercorn. Actually, no single highland Ethiopian with straight hair was measured in the author’s series, although one apparently straight-haired Agau was seen. Among the Amharas, 80 per cent were called “curly,” and the rest “straight,” according to native terminology; among the Gallas the same 20 per cent of “straight” were found, while among the Sidamos this rose to 30 per cent. Actually, the gofari class included both curly hair in a Hadhramaut sense, and frizzly hair of a negroid character. Hair which the Ethiopians themselves considered negroid was confined to a few individuals who were to all purposes pure negroes, and undoubtedly slaves.

According to our own classification, 40 per cent of the Amharas have non-negroid, wavy or curly hair,66 and the rest frizzly; the non-negroid class among the Gallas is 30 per cent, among the Somalis 86 per cent. Some of the Somalis actually have straight hair. Although our series of Sidamos is too small to be reliable, it indicates that these people are not as frequently negroid in hair form as are the Amharas.

The latter, however, show their predominantly non-negroid character in the distribution of the pilous system; they have the most frequent baldness, beards which are often heavy, and a strong minority of heavy body hair; while the Gallas and Sidamos are less bearded and less hairy, and the Somalis, with beards comparable to those of southern Arabs, are almost glabrous on the body. Black hair is, of course, characteristic of all groups; a sporadic individual with dark brown or red-brown hair may be found, however, among all of them. The beard shows no difference from the head hair.

In eye color mixtures between several brunet strains are apparent. The Amharas have 47 per cent of dark brown and 11 per cent of light brown irises, with 39 per cent of mixtures between these two, with a light brown iridical background overlaid by rays of zones of dark brown; among the Gallas the same proportions of the same types are found. Among the Sidamos, black eyes begin to appear, and the dark brown shade is in the great majority, while among the Somalis 32 per cent are black and 56 per cent dark brown. In all groups an occasional case of mixed blond eyes occurs, with a green-brown or gray-brown mixture, but these form no more than 2 per cent of the whole.67 They indicate the persistance of the minority tendency to eye blondism endemic in the Mediterranean racial stock, rather than any northern admixture.

The external eye form varies between the different groups in proportion of negroid blood; the Amharas and the Somalis have few eyefolds, little obliquity, a medium to slight opening height; among the Gallas and Sidamos, the pseudo-mongoloid68 negroid internal fold is occasionally seen, and a strong minority has oblique and wide open eye slits. Similarly, the eyebrows are thickest and most concurrent among Amharas and Somalis.

Browridges are moderate, in a western European sense, or heavy, in over half of the Somali series; the Amharas are slight to moderate, the Gallas and Sidamos slight or absent. Foreheads are usually high among Amharas, and progressively lower among Gallas and Sidamos; the slope is most variable among the Amharas, among whom all forms are frequent; least variable among the Somalis, among whom it is usually slight. On the whole the more negroid have the greatest slopes.

Considerable differences are seen in nose form between the different peoples; the most European forms are found among the Somalis and Amhara, while the Sidamo nose is for the most part negroid in morphology. The Somali noses, although they vary between an extremely leptorrhine and a negroid extreme, assume a normal distribution when tabulated by individual criteria. The mean is a moderate root height, narrow to medium root breadth, moderate bridge height, narrow to moderate bridge breadth, a straight profile a thin tip, which is inclined slightly upward, medium wings, with thin to medium, slightly oblique nostrils. Although individual Somalis are beaky in nasal appearance, the impression of the group as a whole, and especially of the least negroid element, is that of a straight profile and moderate bridge height; in other words, of a classic Mediterranean nose form.

The noses of the Amharas, while very variable, are as a rule higher in root and bridge, and at the same time broader, thicker tipped, and often inclined downward, with a tendency to flaring nasal wings, and highly excavated nostrils. The Amharic nasal profile is again usually straight. The Galla noses are like those of the Amharas, with a slightly higher ratio of broad and flaring forms. Among the Sidamos, thick tips, flaring wings, and low roots and bridges are actually in the majority, although convex profiles are more frequent than among the less negroid groups. The Sidamo nose is morphologically as well as metrically a hybrid negro-white organ, such as is frequently seen among American negroes.

In all groups, including the Somalis, thick lips are more numerous than thin ones, both integumentally and membranously; lip eversion is also characteristically great in all of them, as is a prominent lip seam. Really thin lips exceed 10 per cent only among the Amharas. All of the groups show some degree of prognathism; facial prognathism is approximately 10 per cent in all but the Sidamos, among whom it is greater; alveolar prognathism is present among all but Sidamos, to the extent of 25 per cent; among the Sidamos almost half are prognathous. The chin is as prominent as among most white men in over 60 per cent of all but Somalis, among whom it is characteristically receding. Frontal projection of the malars is slight in all groups; lateral projection is often pronounced among the Gallas and Sidamos, seldom so among Amharas and Somalis Prominence of the gonial angles is most frequently marked among Amharas, never among Somalis.

Negroid traits are seen sometimes in the ear—among Sidamos the most and Amharas the least. The negroid ear has a small, soldered lobe, and an excessive roll to the helix. It rarely slants, while the ears of Amharas and especially of Somalis are characteristically set at an angle to the vertical.

Among all of these peoples differences in racial as well as contitutional type is seen, even among the relatively homogeneous Somalis. Here the bulk of the population gravitates between two end types. The more numerous of these two is typified by a long, thin, bodily form with extremely narrow hands and feet, with thin, gracefully built bodies which, among the women, attain a degree of beauty seldom seen in Europe, with high, conical breasts in the women, totally unlike the pendulous negroid udders so common among Gallas and Amharas, and with th characteristically narrow faces and noses typical of the Somali. The other end type is an ordinary prognathous, thick-nosed, wide-eyed negro. About one Somali out of five seems to have a strong strain of negroid blood; in the others it is for the most part dilute. A few individuals among the Somali69 are lighter skinned, brachycephalic, curly haired, and identical in almost all respects with the typical Hadhramis of southern Arabia. They undoubtedly represent the strain of the missionaries who converted the Somalis to Islam, and who founded the present tribes and families. They are, needless to say, rare.

Among the Amharas there is one very impressive type with a relatively light skin color, a high, wide, sloping forehead, very frizzly hair, a high-bridged nose with a thick, depressed tip, and a long, rather bony face. The total effect is incipiently Papuan, and one feels that a veddoid-negroid cross is indicated, in combination with various amounts of both Arabian and Ethiopian varieties of Mediterranean. The linkage in this type of frizzly hair with these exaggerated facial characters seems to show a genetic realignment of some interest. This type is rare among Hamitic-speaking Ethiopians, who conform for the most part to Mediterranean or negroid facial patterns, in various degrees of solution and in various combinations.

Except for the peculiar behavior of the frizzly hair form among the Amharas, white racial traits, on the whole, seem to be linked together. Among the Somalis, straight or wavy hair is usually fine, inclined to baldness on the head, moderate to heavy on the beard and present on the body; frizzly or woolly hair is of medium texture and scanty on beard and body; curly, Hadhramaut-style hair is often coarse, but is intermediate between white and negroid hair in quantity and distribution. Among both highland Hamites and Somalis, the lighter skins usually go with narrower noses, and straighter hair; dark brown eyes are strongly associated with narrow noses, black eyes with broad ones.

On the basis of these correlations, it is evident that the partly negroid appearance of Ethiopians and of Somalis is due to a mixture between whites and negroes, and that the Ethiopian cannot be considered the representative of an undifferentiated stage in the development of both whites and blacks, as some anthropologists would have us believe. On the whole, the white strain is much more numerous and much more important metrically, while in pigmentation and in hair form the negroid influence has made itself clearly seen. This study of Ethiopians and Somalis has served to bring out the principle that metrical similarities of a racial order have little reference to the soft parts, since Somalis, Gallas Arabs, Berbers, Norwegians, and Englishmen may all be closely related in measurements, and at the same time fall at world extremes in pigmentation and in hair form. Within the Mediterranean racial family there is every variation in these external features between a Nordic and a Somali.

The northern relatives of the Somalis, the Afar or Danakil, seem to resemble them closely both metrically and morphologically.70 If one may hazard a guess from inadequate material, they are even less frequently negroid than are the Somali. The Baria and Cunama, the Sudanic-speaking tribes of Eritrea, are of moderate stature, and are small headed; they are a negroid-Hamitic mixture in which the old Sudanese negroid element is strong.71

Of great importance from the standpoint of the history of Hamitic-speaking peoples in North Africa are the various tribal divisions of the great Beja people, who live to the east of the Nile from Eritrea north into Upper Egypt. Some of them now speak Tigré, others Arabic, but their original speech is Cushitic, and their racial relationship seems to be with the Somalis and Danakils for the most part. Some of them, such as the Haddendoa, have been largely mixed with Sudanese negroes; the less mixed, such as the Beni Amer in northern Eritrea, and the Bishari in the Egyptian desert, represent a fairly uniform type which Seligman compares to the predynastic Egyptians.72

This type is, in its least negroid form, of moderate stature, with tribal means ranging from 164 to 169 cm., and comparable in head dimensions and in facial and nasal breadths with the Somalis, although some tribes are smaller headed. The characteristic narrow jaw of the Somalis is also typical here. The skin color is usually somewhere between a bronze-like reddish-brown and a light chocolate, probably in the lighter part of the rather narrow Somali range; the hair, when not frizzly, is sometimes straight but is usually curly or wavy; and the nasal profile is, like that of the Somalis, usually straight. The physical type of the present-day northern Beja of the Egyptian desert does not exactly fulfill the specifications of the peoples who, as we shall see shortly, must have brought Hamitic speech and Hamitic culture into North Africa in antiquity, but it approximates the general racial position of these Hamitic culture bearers. The presence of the Beja and their apparent antiquity indicate that the desert country east of the Nile and west of the Red Sea has long been a corridor for northward movements by people adapted to desert living, just as the Nile Valley itself, in its reaches below Khartum, may have been a corridor for early agriculturalists.

Notes:

55 Vavilov, N., Studies on the Origin of Cultivated Plants.

56 Asiatic in the sense that it must have been domesticated in Asia, where wild camels are still found. It evolved, of course, in America.

57 Meillet, A., and Cohen, M., Les Langues du Monde; Langues Chamito-Semitiques, pp. 81—151.

58 Information given me by Professor O. Menghin.

59 See Chapter II pp. 44—46; Chapter III, pp. 57—59.

60 The principal works on the physical anthropology of the living in this region are:

Castro, L. de, Nella Terra del Negus, vol. 2, pp. 342—477.

Frasetto, F., AnthPr, vol. 10, 1932, pp. 161—187.

Garson, J. G., Appendix to Bent, T. J., The Sacred City of the Ethiopians, pp. 286—296.

Klimek, S., APA, vols. 60—61, 1930—31, pp. 358—381.

Koettlitz, R., JRAI, vol. 30, 1900, pp. 50—55.

Lester, P., Anth, vol. 38, 1928, pp. 61—90, 289—315.

Leys, N. M., and Joyce, T. A., JRAI, vol. 43, 1913, p. 195.

Puccioni, N., APA, vol. 41, 1911, pp. 295—326; vol. 47, 1917, pp. 13—164; vol. 49, 1919, pp. 41—223; vol. 53, 1923, pp. 25—68; Anthropologia e Etnografia delle Genti della Somalia.

Radlauer, C., AFA, vol. 41, 1914, pp. 451—473.

Verneau, R., Appendix in Duchesne-Fournet, Mission en Ethiopie.

In addition to these, the author has used, in the following exposition, a MS. of his own, awaiting publication, and entitled: Contribution to the Study of the Physical Anthpology of the Ethiopians and Somalis, based on a series of 100 Ethiopians and 80 Somalis measured in 1933—34.

Principal works on the craniology of this region are:

Castro, L. de, APA, vol. 41, 1911, pp. 327—339.

Cipriani, L., APA, vol. 53, 1926, pp. 11—24.

Sergi, S., Crania Habessinica.

Verneau, R., Anth, vol. 10, 1899, pp. 641—662.

Works on the Danakil, Baiia, Cunama, and Beja are listed later.

61 From statistical analysis of author’s unpublished material.

62 From several different series.

63 Schlaginhaufen 0., AJKS, vol. 9, 1934, PP. 265—273.

64 Verneau’s mean is 75.

65 De Castro, in his 1915 study of Ethiopians, gives cephalic index means of 73.9 for Tigré, 75.4 for Shoa, 80.7 for Amhara, and 83.2 for Gojjam. The Amhara series is represented by 50 men, the Gojjam series by 47. Garson finds a mean C. I. of 81.4 for 12 Amhara men measured by Bent. Against these positive evidences of brachycephaly stands the fact that in none of the composite series of Amharic-speaking Ethiopians, which include Gojjam and Amhara men, are brachycephalic individuals found in sufficient numbers to support these figures. Verneau, out of a series of 83, of which 29 are Gojjamites, finds a mean C. I. of 74.9, and a range of 67—82. In my own smaller series the highest C. I. is 81; C. I.’s of 4 Gojjam men were 74, 76, 77, 80. Both Frasetto (1932) and Klimek (1930—31) fail to find brachycephaly in composite Abyssinian series. At present it is impossible to confirm or refute de Castro’s figures.

66 According to Fischer’s findings, our “curly” could be called a negroid-white mixed form.

Fischer, E., Die Rehobother Bastards.

67 Higher percentages have been reported among Amharic speakers in some of the northern kingdoms.

68 Seligman, C. G., and B. Z., Pagan Tribes of the Nilotic Sudan, p. 20.

69 I measured but one, Puccioni gives photographs of several.

70 Bouchereau, A., Anth, vol. 8, 1897, pp. 149—164.

Santelli, BSA, Paris, ser. 4, vol. 4, 1893, pp. 479—501.

71 Pollera, A., I Baria e I Cunama. Pollera’s data make both Baria and Cunama leptorrhine, a supposition which his photographs belie. His nasal breadth technique, and his bizygomatic, are both obviously erroneous.

72 Seigman, C. G., JRAI, vol. 43, 1913, pp. 593—705.

See also:

Chantre, E., BSAL, vol. 18, 1899, pp. 138—141. Also, résumé in Anth, vol. 13, 1902, pp. 122—123.

Murray, G. W., JRAI, vol. 57, 1927, pp. 39—53

www.theapricity.com/snpa/chapter-XI8.htm

The Mediterranean race in East Africa

In the present section we shall consider what is today a second southern periphery of the white racial stock; peripheral in this case to the world of the African Negro. East Africa, with its highland plateaux of Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Kenya, and with its treeless grasslands, forms an environmental zone suitable for the economies of highland agriculture and of pastoral nomadism. Its early connections lie with the north and east, with Egypt and Arabia, rather than with the equatorial forests to the west.

The highlands of Ethiopia, according to studies conducted by economic botanists, seem to contain a number of indigenous varieties of cultivated cereals and legumes.55 It is possible, but by no means established, that these highlands formed one of the primary centers of Old World agriculture, in which the Neolithic economy originated. It is also possible that part of the agricultural impulse which initiated the high civilization of ancient Egypt was derived from this source.

Later than the development of highland agriculture in East Africa was the introduction and diffusion of pastoral nomadism. The cattle complex, with its elaborate set of social restrictions and of social differentiation on the basis of wealth in herds, was introduced from India by way of southern Arabia, along with the humped zebu, at some none too distant period, probably as late as the first millennium B.C. Its diffusion passed southeastward into the Lake Region, where it was taken up by Bantu peoples and spread, in modern times, as far south as the Cape of Good Hope, where an earlier version of the same complex had already arrived, in the hands of the Hottentots.

In the Horn of Africa region, however, and northward into Egypt, the humped cow is replaced by the more thirst-resisting camel; camel nomads are found in all regions in which agriculture is impractical. The antiquity of camel nomadism in East Africa is unknown, but it cannot be as old as in Arabia, for the camel is an Asiatic animal.56 Camels did not appear in any numbers in North Africa east of the Nile before 300 A.D., but they must have been earlier than that in East Africa, having been introduced, at some unknown period, from Arabia by way of Suez, of the Bab el Mandeb, or simply across the Red Sea.

The living peoples with whom this section is concerned live by all three economies mentioned—highland agriculture, cattle nomadism, and camel nomadism. They are the whites and near-whites who live east of the equatorial forests, of the Nilotic swamps, and of the deep escarpment of he Blue Nile. They are the Gallas, the Somalis, the Ethiopians, and the inhabitants of Eritrea. They speak languages of two stocks—Hamitic and Semitic. Of the two, Hamitic is the older, for Semitic speech was introduced by colonists from the Hadhramaut only a few centuries B.C. The Hamitic linguistic stock is divided into three families of languages: (1) Libico-Berber, (2) Ancient Egyptian and its derivative Coptic, (3) Cushitic. These families seem to be nearly as closely related to Semitic as they are to each other,57 so that a Semito-Hamitic superstock has been postulated, with Semitic as the fourth branch. Ancient Egyptian, according to a recent analysis,58 may have been merely a blend of the other three. The East African Hamites, however, all speak languages of the Cushitic family, and the word Hamitic, when applied to East Africans, is equivalent to Cushitic.

Our knowledge of the racial history of East Africa in antiquity is limited to the southern frontier of the present Hamitic linguistic area. Excavations in Kenya and Tanganyika have uncovered remains of a tall, extremely long-headed, Mediterranean racial type, with a tendency to great elongation and narrowness of the face, in pre-Neolithic times. In Mesolithic times, if not earlier, some of these Mediterranean skeletons show evidence of negroid admixture.59 The country east of Lake Victoria may be taken as the southern boundary of the area occupied by this race, since to the south all known sapiens skeletal remains belong to the ancestors of Bushmen. The center of this area, and its northern boundary, are unknown, owing to the lack of archaeological work in Ethiopia and the eastern Sudan. The present distribution of a similar and without doubt derivative racial type coincides with that of Hamitic languages, and for that reason the term “Hamitic Race,” has been frequently employed.

Linguistic map of the East African Hamitic Area

The Cushitic languages of East Africa and of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan are shown in parallel line representation. The Semitic languages of this region which are derived from Geez are designated by cross-hatching. It should be noted that Tigrigna is the language of Tigré Kingdom; the Tigré language, however, is a related coastal speech. Sudanese Negro languages are shown by means of large dots, Arabic by means of vertical crescents. (Adapted from Meillet and Cohen, Les Langues du Monde.)

The living inhabitants of the Abyssinia-Somaliland-Eritrea area may be divided into the following groups:

(1) The Highland Cushites: Descendants of the pre-Semitic agricultural population of the northern Ethiopian plateau, speaking early Cushitic dialects. The most numerous and best known of this scattered group are the Agaus, peasants and agricultural serfs living mostly in the kingdom of Gojjam, in the Lake Tsana country.

(2) The Sidamos: The corresponding pre-Semitic agricultural population of the present Galla country, living in the midst of Galla tribal territories, and in small separate kingdoms of their own, in southwestern Ethiopia. The best known Sidamo state is that of Kaffa, whose name has been given to coffee. Throughout the Galla country, the numerous peasant class consists largely of linguistically altered Sidamos.

(3) The Amharas: This is a general name applied to the Ethiopians proper, members of the four kingdoms of Tigré, Amhara, Gojjam, and Shoa. The Guraghes, who live south of Addis Ababa, speak Amharic, as do all the others named except the Tigrés, whose language is a parallel derivative of Geez. These people are the descendants of the Hadhrami invaders of the late pre-Christian era, and were, until the Italian conquest of 1935—37, the dominant people of Ethiopia.

(4) The Gallas: The inhabitants of most of southwestern Ethiopia, including the country as far north and east as Addis Ababa, are Gallas; descendants of a warlike confederation of nomadic tribes who invaded Ethiopia from the southwest in the sixteenth century. The original Gallas, who came in great numbers, were cattle people with the traditional East African dislike for agriculture or menial occupations, and settled down in their present territory as aristocrats. Galla society today is divided into four classes: the Oromo, or Galla proper, the aristocrats; the Tumtu or blacksmiths, the subservient class of artisans who are also farmers; the Faki, a low caste of tanners; and the Watta, outcaste hunters who live in separate villages. The Oromo have, for the most part, submitted to the pursuit of agriculture, while continuing at the same time their cattle raising.

(5) The Somalis: The whole Horn of Africa, including the three Somali lands and the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, is occupied by various tribes of Somalis, nomadic Hamites who profess Islam and claim descent from Arabian missionaries. Their origin is not clearly known, but it is evident that there must have been some Galla as well as Arabian mixture, grafted onto a local Hamitic population.

(6) The Danakil (also called Afar): In southwestern Eritrea and adjacent parts of the desert of northeastern Ethiopia, as well as in part of French Somaliland, live the Danakil, tribesmen culturally related to the Somalis, who also claim Arabian ancestry. North of the Danakil in Eritrea live other tribes of the same general type. The Somalis, Danakil, and their northern relatives form part of a continuous belt of nomadic Hamites reaching from the Horn of Africa to Egypt; the northern representatives, however, from the Eritrean Beja to the Egyptian Bisharin, have been subjected to strong admixture with Sudanese negroes.

(7) Negroes in Hamitic Territory: In Eritrea the tribes of Baria and Cunama, in the midst of Hamitic-Tigré territory, probably represent, in the linguistic sense at least, and eastward thrust of Sudanese negroes. In Ethiopia proper many Shankalla, negroes brought as slaves from the Blue Nile country, have propagated both as a slave population and through mixture. In Italian Somaliland, it is said that some of the slave tribes subservient to the Somalis speak Bantu. The speech of the Wattas may also be neither Hamitic nor Semitic.

The study of the physical anthropology of this ethnologically and historically complex region may be said to have barely begun; nevertheless it has progressed far enough to warrant reasonably accurate statements as to the racial characters of the more numerous and better known peoples.60 Before proceeding further, it may be well to state that all of the peoples of this “Hamitic” area, whether Hamitic or Semitic in speech, represent a blend in varying proportions between Mediterraneans of several varieties, especially of the tall, Atlanto-Mediterranean group, and negroes. Other elements include, of course, the Veddoid brought in solution from southern Arabia; there is also a possibility of traces of dilute pygmy and Bushman blood in southwestern Ethiopia and Somaliland, although neither of these has been proved. Needless to say, the Gallas and Amharas have mixed with each other greatly in the regions in which they have been in contact; both the Amharas and Gallas have absorbed the earlier Cushitic agricultural peoples in great numbers. The most important single influence has been the infiltration of negroes, through the slave trade, into the entire Ethiopian plateau region. So extensive has this infiltration been that it is unlikely that a single genetic line in the entire Horn of Africa is completely free from negroid admixture; but individuals may be found among the Amharas, Gallas, and Somalis who show no visible signs of negro blood. These individuals are extremely rare. On the whole the negroid element in the Hamitic cannot be much more than one-fourth of the whole, but it has penetrated every ethnic group and every social level. Just when this penetration had become complete we do not know, but one suspects that it had already occurred by the sixth century A.D., when the Ethiopians ruled the Yemen. The Gallas, despite their tradition of descent from white men, were already partly negroid at the time of their arrival in Ethiopia.

Despite this negroid penetration, and despite a mixture between non-negroid elements, the four ethnic Units of Amharas, Gallas, Sidamos, and Somalis are all statistically distinct from each other.61 What evidence we have for the Agaus suggests that this people constitutes a fifth anthropometric entity. As one would expect, the more purely Hamitic peoples, such as the Agaus, Gallas, and Somalis, are taller than the Amharas. All of these three have stature means ranging from 169 to 174 cm., while 172 cm. seems to be the central mean for all of them. The Semitic speakers range from a mean of 164—167 cm.62 for the Tigré, the most nearly Arabian of the four main groups, to 167—169 cm. for each of the other three, while a series of varied Ethiopians, mostly from Shoa, and measured in Addis Ababa, rose to the mean of 169 cm. This latter figure may reflect Galla mixture—for Addis Ababa is in Galla territory—or selection. The Sidamos, in contrast to the Agaus, are apparently short (164 cm.).

In bodily build and proportions, all groups are much the same. The predominant type is leptosome, with a relative sitting height index of 50 to 51, a relative span of 103, and a relative shoulder breadth of 21. Long legs and relatively short arms, narrow shoulders, and even narrower hips, are the rule. Few Ethiopians of any category are thick-set, and what little corpulence is seen hangs ill on fine-boned frames. The hands and feet of all but the palpably negroid are small and extremely narrow, the lower legs and wrists usually spindly and ill-muscled. This attenuation of the distal segments of the limbs reaches its maximum among the Somalis. The Sidamos, who are by far the most negroid of the Ethiopian peoples, have the broadest shoulders in proportion to their height, and the narrowest hips.

There can be no doubt that the tall stature of the Gallas, Somalis, and Agaus is an old Hamitic trait, since both the negroid Sidamos and the Semites of Hadhramauti origin are much shorter. The tallness of this East African Mediterranean strain stands in contrast to the moderate stature of the Mediterranean Arabs across the Red Sea, and constitutes a characteristic difference between them. The bodily build of the African Hamites is typically Mediterranean in the ratio of arms, legs, and trunk, but the special attenuation of the extremities among the Somalis is a strong local feature,63 which finds its closest parallels outside the white racial group, in southern India and in Australia.

The different groups studied in Ethiopia share a tendency to dolichocephaly or mesocephaly, and to a narrow face form. In the measurements of the head and face, all are fundamentally Mediterranean, and the negroid traits manifested in the soft parts do not reveal themselves in the measurements, except in nose breadth and in the biorbital and interorbital diameters. The heads are larger than those of the Yemeni Mediterraneans; Amharas (in the sense of Semitic-speaking Abyssinians) have vault dimensions of 194 mm. (length) by 150 mm. (breadth) by 127 mm. (height); these figures could apply as well to Nordics as to Abyssinians. The mean cephalic index of 77 or lower64 for Amharic speakers is in the dolichocephalic to low mesocephalic class; the smaller diameters and higher index of the present-day Hadhramaut population seem to have yielded to the greater size and dolichocephaly of the indigenous Hamitic farmers, as far as the total group is concerned. There is, however, some evidence that while the Tigré people are strongly dolichocephalic, brachycephaly may be common in the kingdoms of Gojjam and Amhara.65

The Gallas are on the whole smaller headed than the Amharas, but also mesocephalic. Mesocephaly is also the prevalent head form of both Agaus and Sidamos; among the latter the mean cephalic index is 78, and there is a definite brachycephalic minority. So far the inhabitants of the Abyssinian plateau, whatever their speech and ethnic origin, are dolichocephalic or mesocephalic, and comparable to Mediterraneans elsewhere, especially, as we shall later see, to North African Berbers, as well as to North European Nordics. Among the Sidamos, however, the vault is lower (124 mm.) than among Amharas and Gallas. The Somalis, as contrasted with the highland bloc, are smaller headed and purely dolichocephalic, with vault dimensions of 192 mm. (length) by 143 mm. (breadth) by 123 mm. (height), and a mean cephalic index of 74.5. In this they resemble closely the finer Mediterranean type in Yemen, and some of the northern Bedawin.

Facially this division between highianders and Somalis is accentuated. The highlanders have minimum frontal means of 104 mm. to 106 mm.; the Somalis of 102 mm. The bizygomatics of the first group fall at 134—136 mm., of the Somalis at 131 mm. The bigonials of the highianders have means of 101—102 mm., of the Somalis, 96 mm. All are narrow faced, but the Somalis approximate a world extreme. The forehead is in all groups notably wider than the jaw, which reaches a record in narrowness among the Somalis. In face breadths as in vault dimensions the less extreme highland Ethiopians might as well be Nordics as negroids.

The total face heights of the four groups under consideration range from 122 mm. to 124 mm.; the upper face heights from 71 mm. to 74mm. It is interesting to note that the Sidamos, who are the most negroid, have the broadest foreheads, bizygomatics, and bigonials, the longest menton-nasion heights, and by far the longest upper face heights, of the entire group. It is the Somalis whose upper face height is shortest. All four are leptoprosopic and leptene, the Somalis hyperleptoprosopic.

The noses of Somalis, Amharas, and Gallas are leptorrhine, with nasal indices of 66, 68, and 69, respectively. This regression indicates with some accuracy the relative amounts of negro blood. The Sidamos, with an index of 71, are mesorrhine and the most negroid. In accordance with the principle that the most negroid have the longest as well as the broadest faces, the Sidamos have the longest and broadest noses, with a mean height of 55 mm., and breadth of 39 mm. The Somalis, whose noses are narrowest, also have the smallest, 52 mm. by 34 mm.

In the measurements of the external eye the Somalis differ again from the highlanders; their mean interorbital diameter of 31 mm. is narrow, while that of the highianders, 34—35 mm., approximates a negroid condition. In the biorbital, the distance between the outer eye corners, the Somalis are narrowest, with 91 mm.; the Sidamos the broadest with 96 mm.

Our Survey of the metrical characters of the inhabitants of the Hamitic racial area has brought several facts to light; the agricultural population of the Ethiopian highlands, both indigenous and imported from Arabia, belongs to a tall, dolichocephalic to mesocephalic, leptoprosopic, moderately leptorrhine race, which is Mediterranean in metrical position and cannot be distinguished, on the basis of the more commonly taken measurements, from blond and brunet Mediterraneans of Europe and North Africa. The Somalis, on the other hand, belong to an extreme racial form; extremely linear in bodily build, extremely narrow-headed and narrow-faced, with a special narrowness of the jaw. The relationship of the Somalis, on metrical grounds, is with some of the peoples of India as much as with the Mediterraneans elsewhere. The leptosome tendency, and the narrowness of the face, remind one of the same tendency found among the mixed Bedawin group of the Hadhramaut. It cannot be attributed to negro-white mixture, for that phenomenon, as witnessed among the Sidamos, has produced a heaping of characters, resulting in an enlargement of both sagittal and lateral diameters of the face, in some cases in excess of either the Hamitic white or the negroid parent. Upper face height and nose height are especially affected. The Somali face and nose are not long, they are merely narrow. The extremely long faces and noses found among the Ba-Hima, the noble class of the Baganda, and supposedly of Galla origin, have acquired a social value, and far exceed those of the Somali. In this tendency to attenuation of the face, we are reminded of Oldoway man and some of the Elmenteita skeletons. This tendency is an extremely old one in East Africa.

In the skin color of the Arabs, however dark the exposed and tanned parts might be, the unexposed epidermis was always considerably lighter. A fundamental difference between Arabs and Ethiopians is seen in this feature, for the latter are usually the same in skin color all over. In fact, the foreheads of Ethiopians are in some instances lighter than their shirt-protected bodies. In the three highland groups of Amharas, Gallas, and Sidamos, the Amharas are lightest skinned, with the majority of shades concentrated in the medium brown category, between von Luschan #21 and #25; individually the series runs as light as #13, a brunet-white, which is approximately the color of the former Emperor, Hailie Selassie. At the other extreme it reaches #34, which is almost jet black, nearer the color of the great Emperor Menelik II. Thus among the Amharas almost the entire range of human skin color intensity is covered, with the exception of rosy or pinkish-white, which probably does not exist among Ethiopians. The Gallas run somewhat darker, with their concentration in the medium to chocolate-brown class, between #22 and #29; their range is somewhat less than that of the Amharas, and the rare brunet-white of the former is in some cases replaced by a yellow of Bushman intensity. Most of the Sidamos are darker than #30, and are thus really dark brown or black.

So far, the progression in skin color has followed that of relative amounts of negro blood, with an immense range covered; the inheritance of skin color in the Ethiopian highlands is not strictly Mendelian in a simple sense, nor is it by any means a case of ordinary blending. If there was ever a rosy-white shade in the non-negroid element, it has long since disappeared. Among the Somalis, however, an entirely different situation is found, for the majority are lumped around the von Luschan #29. Numbers 27 and 30 account for most of the others; hence there is a single and characteristic Somali color, which is a rich, glossy, chocolate-brown, which accounts for seven-eights of the entire Somali group. A very few are darker, and individuals are as light as light brown, in a very few cases as light as Arabs. The contrast between highland Ethiopians and Somalis in skin color is so great that one must postulate that the original non-negroid narrow-bodied and narrow-faced strain which the living Somalis represent was not white skinned in any sense of the word, for the Somalis are the least negroid people in East Africa.

The Ethiopians themselves are extremely conscious of differences in skin color, and divide themselves into four groups: “Yellow,” “Yellow-Red,” “Red,” and “Black.” These groups do not correspond very well with the von Luschan scale, but represent the product of centuries of local experience, and are perhaps more significant from the genetic standpoint. A jury of Amharas and Gallas called 20 per cent of the former “Yellow,” as against 8 per cent of the latter; only 2 per cent of either was “Black.” In both, the “Red” class was the most numerous; with 47 per cent of Amharas, and 70 per cent of Gallas. Most of the few Sidamos studied are evenly divided between “Red” and “Black.” This system could not be applied to the Somalis, whose characteristic hue defied classification.

In hair form the Ethiopians also have their own system, which hardly agrees with ours. It has three divisions; lüchai, meaning “straight,” gofari, meaning “curly,” and another term which signifies extremely negroid, or peppercorn. Actually, no single highland Ethiopian with straight hair was measured in the author’s series, although one apparently straight-haired Agau was seen. Among the Amharas, 80 per cent were called “curly,” and the rest “straight,” according to native terminology; among the Gallas the same 20 per cent of “straight” were found, while among the Sidamos this rose to 30 per cent. Actually, the gofari class included both curly hair in a Hadhramaut sense, and frizzly hair of a negroid character. Hair which the Ethiopians themselves considered negroid was confined to a few individuals who were to all purposes pure negroes, and undoubtedly slaves.

According to our own classification, 40 per cent of the Amharas have non-negroid, wavy or curly hair,66 and the rest frizzly; the non-negroid class among the Gallas is 30 per cent, among the Somalis 86 per cent. Some of the Somalis actually have straight hair. Although our series of Sidamos is too small to be reliable, it indicates that these people are not as frequently negroid in hair form as are the Amharas.

The latter, however, show their predominantly non-negroid character in the distribution of the pilous system; they have the most frequent baldness, beards which are often heavy, and a strong minority of heavy body hair; while the Gallas and Sidamos are less bearded and less hairy, and the Somalis, with beards comparable to those of southern Arabs, are almost glabrous on the body. Black hair is, of course, characteristic of all groups; a sporadic individual with dark brown or red-brown hair may be found, however, among all of them. The beard shows no difference from the head hair.

In eye color mixtures between several brunet strains are apparent. The Amharas have 47 per cent of dark brown and 11 per cent of light brown irises, with 39 per cent of mixtures between these two, with a light brown iridical background overlaid by rays of zones of dark brown; among the Gallas the same proportions of the same types are found. Among the Sidamos, black eyes begin to appear, and the dark brown shade is in the great majority, while among the Somalis 32 per cent are black and 56 per cent dark brown. In all groups an occasional case of mixed blond eyes occurs, with a green-brown or gray-brown mixture, but these form no more than 2 per cent of the whole.67 They indicate the persistance of the minority tendency to eye blondism endemic in the Mediterranean racial stock, rather than any northern admixture.

The external eye form varies between the different groups in proportion of negroid blood; the Amharas and the Somalis have few eyefolds, little obliquity, a medium to slight opening height; among the Gallas and Sidamos, the pseudo-mongoloid68 negroid internal fold is occasionally seen, and a strong minority has oblique and wide open eye slits. Similarly, the eyebrows are thickest and most concurrent among Amharas and Somalis.

Browridges are moderate, in a western European sense, or heavy, in over half of the Somali series; the Amharas are slight to moderate, the Gallas and Sidamos slight or absent. Foreheads are usually high among Amharas, and progressively lower among Gallas and Sidamos; the slope is most variable among the Amharas, among whom all forms are frequent; least variable among the Somalis, among whom it is usually slight. On the whole the more negroid have the greatest slopes.

Considerable differences are seen in nose form between the different peoples; the most European forms are found among the Somalis and Amhara, while the Sidamo nose is for the most part negroid in morphology. The Somali noses, although they vary between an extremely leptorrhine and a negroid extreme, assume a normal distribution when tabulated by individual criteria. The mean is a moderate root height, narrow to medium root breadth, moderate bridge height, narrow to moderate bridge breadth, a straight profile a thin tip, which is inclined slightly upward, medium wings, with thin to medium, slightly oblique nostrils. Although individual Somalis are beaky in nasal appearance, the impression of the group as a whole, and especially of the least negroid element, is that of a straight profile and moderate bridge height; in other words, of a classic Mediterranean nose form.

The noses of the Amharas, while very variable, are as a rule higher in root and bridge, and at the same time broader, thicker tipped, and often inclined downward, with a tendency to flaring nasal wings, and highly excavated nostrils. The Amharic nasal profile is again usually straight. The Galla noses are like those of the Amharas, with a slightly higher ratio of broad and flaring forms. Among the Sidamos, thick tips, flaring wings, and low roots and bridges are actually in the majority, although convex profiles are more frequent than among the less negroid groups. The Sidamo nose is morphologically as well as metrically a hybrid negro-white organ, such as is frequently seen among American negroes.

In all groups, including the Somalis, thick lips are more numerous than thin ones, both integumentally and membranously; lip eversion is also characteristically great in all of them, as is a prominent lip seam. Really thin lips exceed 10 per cent only among the Amharas. All of the groups show some degree of prognathism; facial prognathism is approximately 10 per cent in all but the Sidamos, among whom it is greater; alveolar prognathism is present among all but Sidamos, to the extent of 25 per cent; among the Sidamos almost half are prognathous. The chin is as prominent as among most white men in over 60 per cent of all but Somalis, among whom it is characteristically receding. Frontal projection of the malars is slight in all groups; lateral projection is often pronounced among the Gallas and Sidamos, seldom so among Amharas and Somalis Prominence of the gonial angles is most frequently marked among Amharas, never among Somalis.

Negroid traits are seen sometimes in the ear—among Sidamos the most and Amharas the least. The negroid ear has a small, soldered lobe, and an excessive roll to the helix. It rarely slants, while the ears of Amharas and especially of Somalis are characteristically set at an angle to the vertical.

Among all of these peoples differences in racial as well as contitutional type is seen, even among the relatively homogeneous Somalis. Here the bulk of the population gravitates between two end types. The more numerous of these two is typified by a long, thin, bodily form with extremely narrow hands and feet, with thin, gracefully built bodies which, among the women, attain a degree of beauty seldom seen in Europe, with high, conical breasts in the women, totally unlike the pendulous negroid udders so common among Gallas and Amharas, and with th characteristically narrow faces and noses typical of the Somali. The other end type is an ordinary prognathous, thick-nosed, wide-eyed negro. About one Somali out of five seems to have a strong strain of negroid blood; in the others it is for the most part dilute. A few individuals among the Somali69 are lighter skinned, brachycephalic, curly haired, and identical in almost all respects with the typical Hadhramis of southern Arabia. They undoubtedly represent the strain of the missionaries who converted the Somalis to Islam, and who founded the present tribes and families. They are, needless to say, rare.

Among the Amharas there is one very impressive type with a relatively light skin color, a high, wide, sloping forehead, very frizzly hair, a high-bridged nose with a thick, depressed tip, and a long, rather bony face. The total effect is incipiently Papuan, and one feels that a veddoid-negroid cross is indicated, in combination with various amounts of both Arabian and Ethiopian varieties of Mediterranean. The linkage in this type of frizzly hair with these exaggerated facial characters seems to show a genetic realignment of some interest. This type is rare among Hamitic-speaking Ethiopians, who conform for the most part to Mediterranean or negroid facial patterns, in various degrees of solution and in various combinations.

Except for the peculiar behavior of the frizzly hair form among the Amharas, white racial traits, on the whole, seem to be linked together. Among the Somalis, straight or wavy hair is usually fine, inclined to baldness on the head, moderate to heavy on the beard and present on the body; frizzly or woolly hair is of medium texture and scanty on beard and body; curly, Hadhramaut-style hair is often coarse, but is intermediate between white and negroid hair in quantity and distribution. Among both highland Hamites and Somalis, the lighter skins usually go with narrower noses, and straighter hair; dark brown eyes are strongly associated with narrow noses, black eyes with broad ones.

On the basis of these correlations, it is evident that the partly negroid appearance of Ethiopians and of Somalis is due to a mixture between whites and negroes, and that the Ethiopian cannot be considered the representative of an undifferentiated stage in the development of both whites and blacks, as some anthropologists would have us believe. On the whole, the white strain is much more numerous and much more important metrically, while in pigmentation and in hair form the negroid influence has made itself clearly seen. This study of Ethiopians and Somalis has served to bring out the principle that metrical similarities of a racial order have little reference to the soft parts, since Somalis, Gallas Arabs, Berbers, Norwegians, and Englishmen may all be closely related in measurements, and at the same time fall at world extremes in pigmentation and in hair form. Within the Mediterranean racial family there is every variation in these external features between a Nordic and a Somali.

The northern relatives of the Somalis, the Afar or Danakil, seem to resemble them closely both metrically and morphologically.70 If one may hazard a guess from inadequate material, they are even less frequently negroid than are the Somali. The Baria and Cunama, the Sudanic-speaking tribes of Eritrea, are of moderate stature, and are small headed; they are a negroid-Hamitic mixture in which the old Sudanese negroid element is strong.71

Of great importance from the standpoint of the history of Hamitic-speaking peoples in North Africa are the various tribal divisions of the great Beja people, who live to the east of the Nile from Eritrea north into Upper Egypt. Some of them now speak Tigré, others Arabic, but their original speech is Cushitic, and their racial relationship seems to be with the Somalis and Danakils for the most part. Some of them, such as the Haddendoa, have been largely mixed with Sudanese negroes; the less mixed, such as the Beni Amer in northern Eritrea, and the Bishari in the Egyptian desert, represent a fairly uniform type which Seligman compares to the predynastic Egyptians.72

This type is, in its least negroid form, of moderate stature, with tribal means ranging from 164 to 169 cm., and comparable in head dimensions and in facial and nasal breadths with the Somalis, although some tribes are smaller headed. The characteristic narrow jaw of the Somalis is also typical here. The skin color is usually somewhere between a bronze-like reddish-brown and a light chocolate, probably in the lighter part of the rather narrow Somali range; the hair, when not frizzly, is sometimes straight but is usually curly or wavy; and the nasal profile is, like that of the Somalis, usually straight. The physical type of the present-day northern Beja of the Egyptian desert does not exactly fulfill the specifications of the peoples who, as we shall see shortly, must have brought Hamitic speech and Hamitic culture into North Africa in antiquity, but it approximates the general racial position of these Hamitic culture bearers. The presence of the Beja and their apparent antiquity indicate that the desert country east of the Nile and west of the Red Sea has long been a corridor for northward movements by people adapted to desert living, just as the Nile Valley itself, in its reaches below Khartum, may have been a corridor for early agriculturalists.

Notes:

55 Vavilov, N., Studies on the Origin of Cultivated Plants.

56 Asiatic in the sense that it must have been domesticated in Asia, where wild camels are still found. It evolved, of course, in America.

57 Meillet, A., and Cohen, M., Les Langues du Monde; Langues Chamito-Semitiques, pp. 81—151.

58 Information given me by Professor O. Menghin.

59 See Chapter II pp. 44—46; Chapter III, pp. 57—59.

60 The principal works on the physical anthropology of the living in this region are:

Castro, L. de, Nella Terra del Negus, vol. 2, pp. 342—477.

Frasetto, F., AnthPr, vol. 10, 1932, pp. 161—187.

Garson, J. G., Appendix to Bent, T. J., The Sacred City of the Ethiopians, pp. 286—296.

Klimek, S., APA, vols. 60—61, 1930—31, pp. 358—381.

Koettlitz, R., JRAI, vol. 30, 1900, pp. 50—55.

Lester, P., Anth, vol. 38, 1928, pp. 61—90, 289—315.

Leys, N. M., and Joyce, T. A., JRAI, vol. 43, 1913, p. 195.

Puccioni, N., APA, vol. 41, 1911, pp. 295—326; vol. 47, 1917, pp. 13—164; vol. 49, 1919, pp. 41—223; vol. 53, 1923, pp. 25—68; Anthropologia e Etnografia delle Genti della Somalia.

Radlauer, C., AFA, vol. 41, 1914, pp. 451—473.

Verneau, R., Appendix in Duchesne-Fournet, Mission en Ethiopie.

In addition to these, the author has used, in the following exposition, a MS. of his own, awaiting publication, and entitled: Contribution to the Study of the Physical Anthpology of the Ethiopians and Somalis, based on a series of 100 Ethiopians and 80 Somalis measured in 1933—34.

Principal works on the craniology of this region are:

Castro, L. de, APA, vol. 41, 1911, pp. 327—339.

Cipriani, L., APA, vol. 53, 1926, pp. 11—24.

Sergi, S., Crania Habessinica.

Verneau, R., Anth, vol. 10, 1899, pp. 641—662.

Works on the Danakil, Baiia, Cunama, and Beja are listed later.

61 From statistical analysis of author’s unpublished material.

62 From several different series.

63 Schlaginhaufen 0., AJKS, vol. 9, 1934, PP. 265—273.

64 Verneau’s mean is 75.

65 De Castro, in his 1915 study of Ethiopians, gives cephalic index means of 73.9 for Tigré, 75.4 for Shoa, 80.7 for Amhara, and 83.2 for Gojjam. The Amhara series is represented by 50 men, the Gojjam series by 47. Garson finds a mean C. I. of 81.4 for 12 Amhara men measured by Bent. Against these positive evidences of brachycephaly stands the fact that in none of the composite series of Amharic-speaking Ethiopians, which include Gojjam and Amhara men, are brachycephalic individuals found in sufficient numbers to support these figures. Verneau, out of a series of 83, of which 29 are Gojjamites, finds a mean C. I. of 74.9, and a range of 67—82. In my own smaller series the highest C. I. is 81; C. I.’s of 4 Gojjam men were 74, 76, 77, 80. Both Frasetto (1932) and Klimek (1930—31) fail to find brachycephaly in composite Abyssinian series. At present it is impossible to confirm or refute de Castro’s figures.

66 According to Fischer’s findings, our “curly” could be called a negroid-white mixed form.

Fischer, E., Die Rehobother Bastards.

67 Higher percentages have been reported among Amharic speakers in some of the northern kingdoms.

68 Seligman, C. G., and B. Z., Pagan Tribes of the Nilotic Sudan, p. 20.

69 I measured but one, Puccioni gives photographs of several.

70 Bouchereau, A., Anth, vol. 8, 1897, pp. 149—164.

Santelli, BSA, Paris, ser. 4, vol. 4, 1893, pp. 479—501.

71 Pollera, A., I Baria e I Cunama. Pollera’s data make both Baria and Cunama leptorrhine, a supposition which his photographs belie. His nasal breadth technique, and his bizygomatic, are both obviously erroneous.

72 Seigman, C. G., JRAI, vol. 43, 1913, pp. 593—705.

See also:

Chantre, E., BSAL, vol. 18, 1899, pp. 138—141. Also, résumé in Anth, vol. 13, 1902, pp. 122—123.

Murray, G. W., JRAI, vol. 57, 1927, pp. 39—53

www.theapricity.com/snpa/chapter-XI8.htm